By Fr. Kelvin Ugwu

This is the fourth and final part of my analysis on Noah’s Ark.

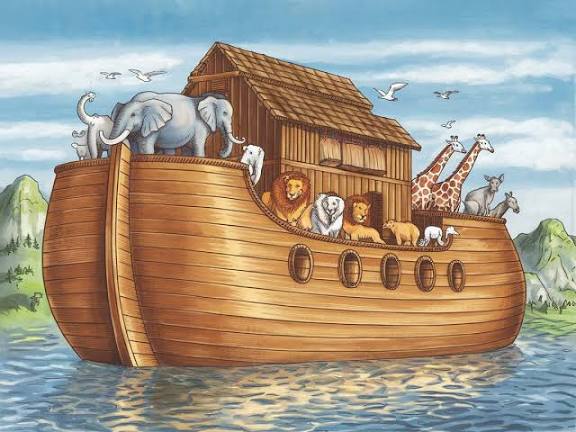

In the first part, I examined the impossibility and illogicality of a strictly literal interpretation of the flood as presented in the Bible. It is logically untenable to claim that a flood covered the entire globe or that only the animals that entered Noah’s Ark survived and later became the source of all biological diversity we have today.

In the second part, I took a historical approach to trace the possible origins of the flood narrative. We saw that similar flood stories existed long before Genesis was written, particularly among the peoples of the ancient Near East. The most famous of these is the Epic of Gilgamesh.

In the third part, I explored how unfair it is to evaluate a text that is nearly three thousand years old using a modern, scientific mindset. The biblical authors did not intend to write a scientific or geographical account. They wrote with a clear purpose, and their original audience understood them within their own cultural and intellectual context.

From all this, my conclusion is simple.

The story of Noah, and Genesis as a whole, was not written to explain how the world works. Genesis is not a science textbook. It is theological literature, written to reveal who God is, who we are, and how we are meant to live.

The biblical authors were not concerned with water volume, animal logistics, or planetary geography. They were addressing deeper and more enduring questions:

Why is the world broken?

Why is there violence?

Does God care?

Does evil have the final word?

This is why:

The flood is not about water.

The ark is not about animals.

The rainbow is not about weather.

The event may have had a historical basis, but its narration goes far beyond the physical elements of water and wood.

The flood represents moral collapse.

The ark represents preservation and refuge.

The covenant represents restraint, mercy, and God’s enduring commitment to life.

The Church, for its part, has never required believers to accept a literal global flood or a wooden ark carrying every animal species. On the contrary, the Church teaches that Scripture must be interpreted according to literary genre, historical context, and authorial intention.

The Second Vatican Council, in Dei Verbum, states clearly that in order to understand Scripture properly, one must consider “the literary forms” and “the conditions of their time and culture.”

In other words, the Church itself rejects rigid literalism.

The Catechism affirms that Genesis employs figurative language to communicate profound truths about creation, sin, and God’s relationship with humanity. It does not bind faith to scientific claims that contradict reason.

Faith and reason are not enemies. The Church has always taught that truth cannot contradict truth.

When believers force Genesis to compete with geology, biology, and anthropology, they set young minds up for crisis. Eventually, science prevails, and faith is wrongly discarded along with poor interpretation.

But when Genesis is allowed to be what it truly is, faith becomes deeper, not weaker.

We stop asking whether kangaroos hopped from Australia to the Middle East.

We stop wondering how penguins survived desert heat.

We stop embarrassing Scripture with questions it was never meant to answer.

So yes, the flood story is not scientific.

Yes, it borrows imagery familiar to the ancient world.

Yes, it uses expansive and universal language.

And yet, it tells the truth.

Not the truth of measurements, but the truth of meaning.

Not the truth of mechanics, but the truth of morality.

Not the truth of water levels, but the truth of human failure and divine mercy.

This is the balance.

We do not insult intelligence in order to protect faith.

And we do not abandon faith in order to honor intelligence.

Any religion that forbids questioning is fragile.

Any faith that fears reason is already wounded.

The Bible does not need to be defended from inquiry. It needs to be read properly.

When the story of Noah is read for what it truly is, it ceases to be a childish tale and becomes a serious reflection on humanity, responsibility, judgment, and hope.

That is where faith and reason finally meet.

I hope this helps. Any question?

We now move on to the next question.