By Fr. Kelvin Ugwu

The story is recorded in Genesis 11. It begins with a striking statement:

“The whole world had one language and a common speech.”

This is interesting because in Genesis 10, just one chapter earlier, the same book already tells us that different languages were in existence. This is mentioned clearly in at least three places: Genesis 10:5, 10:20, and 10:31.

This fact alone already gives Genesis 11 its proper interpretive direction. It tells us that this cannot be a literal account of the origin of all languages. Rather, it is a theological parable, written to explain something deeper.

By the end of the story, it becomes clear that it is addressing the danger of arrogant and centralised human power, with Babylon very much in view.

How do we know this?

Genesis 11:4 says:

“Come, let us build ourselves a city, and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves.”

If one truly wants to understand the Tower of Babel, that sentence is the heart of the problem.

Not the tower. No.

Not the height. No.

But the desire to make a name for themselves.

Ordinarily, making a name for oneself is not necessarily bad. The question, however, is: what kind of name, and on what basis? The biblical writers were writing within a context, and we must read them within that context.

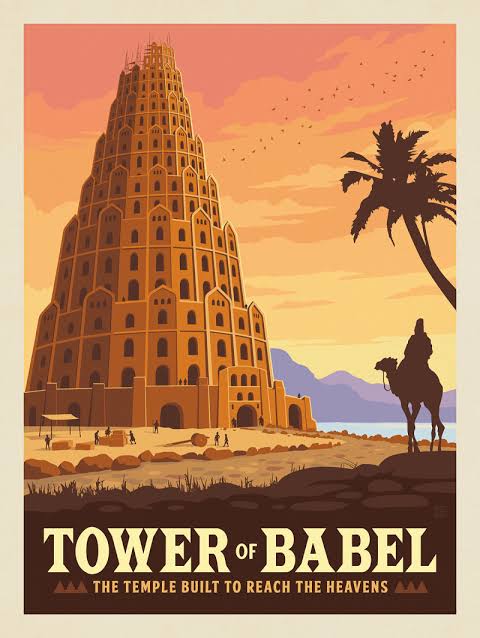

The Tower of Babel story is widely understood to be influenced by the culture of ancient Mesopotamia, especially Babylon.

In ancient Mesopotamia, people built ziggurats. These were massive stepped temple towers made of mud bricks, usually dedicated to a national god. The most famous of them, Etemenanki, literally meant “the house of the foundation of heaven and earth.” It stood at about 90 metres — impressive for its time.

Ziggurats were not built for humans to climb into heaven. They were built to bring the gods down, to localise divine power, and to control religion, gods, politics, and unity from a single centre.

It is from this background that we understand what Genesis means by “making a name for ourselves.” The Babel story is deliberately challenging and rejecting that worldview.

The Tower of Babel is therefore not a story about humans almost reaching God. It is a story about humans trying to replace God and to control God. It is not anti-progress. It is anti-arrogance. It is about pride.

It is also not about heaven being somewhere up in the sky. Catholic theology has never taught that. Heaven is not a location reached by height, bricks, or rockets. Heaven is communion with God.

The true lesson of Babel is simple and uncomfortable: when human beings try to build meaning, unity, and destiny without reference to God, even their greatest achievements become hollow.

The next question is about Jonah in the belly of the fish. . .

#PurestPurity